Lessons in Film History #6 - East Winds. Experimental Cinema beyond the Wall. Poland

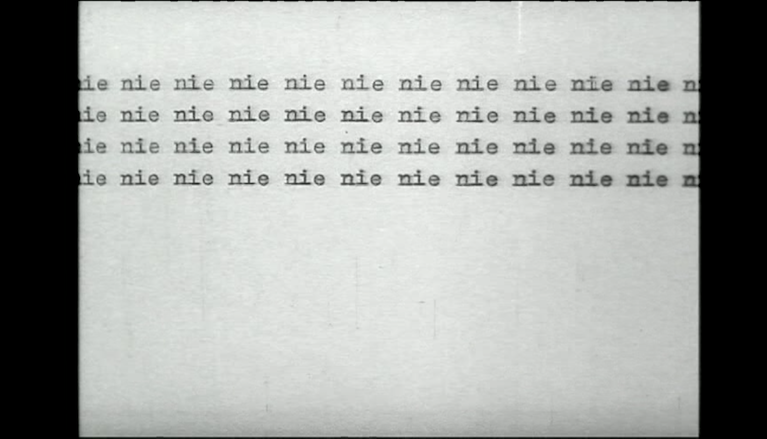

This analytical experiment, due to monotonous, emphatic repetition and multiplication of the word ‘no’ (on the visual and sonic level), was interpreted in Western countries (much to the artist’s surprise) as a protest against communism in Poland.

Founded in 1970 as an academic club at the Leon Schiller National Higher School of Film, Television and Theatre in Łódz ́, Warsztat Formy Filmowej (Workshop of the Film Form) was highly influential in Poland for establishing the paradigm for investigations of “film as film” throughout the 70s, a pioneer group in the context of conceptual artistic practice and analytical art, active in almost all visual creation spheres. Many workshop members later became major figures in Polish contemporary art. While at the WWF, they undertook experiments with the structure of cinematic production, aiming to release it from narrative and literary confines. The WWF members perpetuated avant-garde traditions, presenting a conceptual-analytical attitude, and at the same time acknowledging their ties to Dadaism represented by Stefan and Franciszka Themerson as well as Constructivism of Władysław Strzemi ski and Katarzyna Kobro. For this reason, it seemed natural for them to collaborate with the Łódz ́ Art Museum, at the time managed by Ryszard Stanisławski.

WWF was founded by the students and graduates of the school and included: Wojciech Bruszewski, Paweł Kwiek, Andrzej Rózycki, Józef Robakowski, Zbigniew Rybczynski, Kazimierz Bendkowski, Antoni Mikolajczyk, Janusz Polom, and Ryszard Wasko. As pioneers of video art in Poland and structural cinema in Central and Eastern Europe, these artists refused classical narrative and traditional film media, working instead somewhere between cinematography and contemporary art. Their work proved to be a highly subversive force in Polish experimental film as well as a center of creative rebellion at the workshop, which remained in existence until 1977.

The artists of the group criticized both the university system and the structures of cinematic production, trying to free the film from its narrative codes, to unmask its artificiality, to analyze the foundations of the medium. The critique of cinema as a mindless creation of imaginary worlds went hand in hand with a need for an analysis of the film medium, which often took the form of attempting to reach its foundations and unmasking the ease with which it can be manipulated. On the other hand, a film camera, and later a portable video camera, was becoming a valuable tool in their hands, enabling the group to create an alternative interpretation of reality, different from the one everyone had become accustomed to and which they have adopted ‘naturally’. WFF was remarkable both for the degree of freedom its members enjoyed and the quality of the professional equipment to which they had access. “Within the Studio the members were able to create their very own educational and research curriculum independent of the school’s requirements—whilst at the same time benefiting from its financial help and technical infrastructure. This is the reason why, as art historian Łukasz Ronduda points out, ‘the majority of their radical films were shot in the ‘Hollywood’ format of 35mm.’”

curated by Federico Rossin

In East-European countries, when the Cold War was in full swing, dozens of filmmakers challenged pro-Soviet authorities making experimental films often openly in contrast with regime aesthetics, politics, and economics. This new chapter of the Pesaro “Lessons in Film History” aims to take the audience to a still unexplored continent that has remained buried so far. A full array of surprising works established an overt dialogue with international auteur cinema, mainstream cinema of capitalist countries, and socialist realism of Iron Curtain countries. These productions of the three countries were indeed the result of state funding to film schools during the period of socialism, which didn’t prevent them from getting rid of the codes of propaganda and outright mainstream cinema.

ALL SCREENINGS ARE FREE