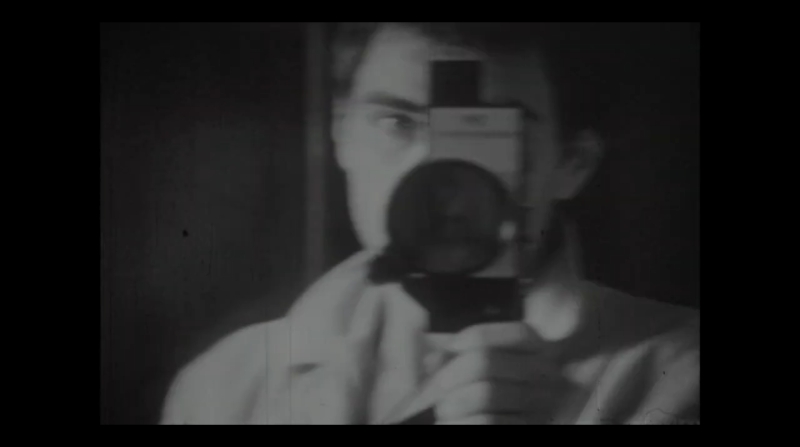

Omaggio a Ali Khamraev

BELYE, BELYE AISTY

Alla presenza del regista, di Eldjon Abbasov per il Film Found of Uzbekistan e di Otabek Akbatov per l’Ambasciata della Repubblica dell'Uzbekistan in Italia.

Kajum refuses to marry the girl whom his parents have chosen for him and quits his home.

He settles in a small Uzbek village, where he falls in love with Malika. She is imprisoned in a combined marriage as well, but then rebels against imposed religious and cultural traditions. The young couple are victim of the villagers’ judgment, as their love is seen as a challenge against centuries-old mores affecting marriages too. This theme was hot in Uzbekistan, and therefore the film was not well received at home. In a recent interview, Khamraev declared that “so far, it has never been released in theatres or broadcast on TV.”

sceneggiatura/script

Odelsha Agishev, Ali Khamraev

fotografia/cinematography

Dilshat Fatkhulin

musica/music

Rumil Vildanov

produzione/production

Uzbekfilm

interpreti/cast

Sajram Isaeva, Bolot Bejshenaliev, Khikmat Latypov, Mokhammed Rafikov, Rassak Khamraev, Rakhim Pirmukhamedov, Saib Khodzhaev, Sajd Alieva, Vakhab Sbdullaev, Ljutfi Sarymsakova, Rustam Sagdullaev.

Film director and writer Ali Khamrayev was born in Tashkent (Uzbekistan, former USSR) in 1937. He attended the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) and was given the Meritorious Artist Award of the Uzbek SSR in 1969. Many of Khamrayev films deal with the civil war and the Basmachi rebellion, including The Extraordinary Commissar / Crezvycajnyj komissar (1970) and The Seventh Bullet / Sed’maja pulja (1972). Other unmissable titles of the director, who now lives in Italy, are The Man Who Loves the Birds / Celovek uchodit za pticami (1975), Without Fear / Bez stracha (1971), Triptych / Triptich (1979), the documentary The Garden of Desires / Sad želanij (1987), and Bo Ba Bu (1998).

Olga Strada

With this tribute to the Uzbekistani film director Ali Khamrayev, the Pesaro Film Festival intends to introduce a lesser-known chapter of the cultural history of a country, Uzbekistan, whose film industry is in fact considered one with that of the Soviet Union. On the other hand, the development of Uzbek cinema mirrors the historical processes of Russia in its distinct phases. Just like the other national film industries of the large organism that was the USSR, Uzbek cinema had a strong expressive identity. Its evolution can be divided into three periods: early 20th century up to the mid-twenties (concomitantly with the modernisation that affected this area of Central Asia as a consequence of Imperial Russia’s colonial politics); from the mid-twenties to 1980 (when a national production company was established in the country: Uzbekfil’m, as it was renamed in 1936, and a specific film language was formed and strengthened); and the last and current period, counting from 1991 after the ‘decolonialisation’ of Russia.

The earliest phase can be distinguished for the immediate success of the Lumière brothers’ invention, followed by the opening of several movie theatres as well as international productions in Tashkent (during the 1910’s, the film operator Félix Mesguich visited those countries and described his impressions in his memoirs Tours de manivelle). Among the earliest founders of Uzbek cinema, mention should be made of Khudaibergen Devanov, who was to become a victim to Stalin’s purges along with other film directors. By the mid-thirties, a film language was now formed which presented marked identity signs, both formal and conceptual, found in the films of Nabi Ganiev, Suleiman Khodjaev, and Ergash Khamrayev (an actor and father of Ali Khamrayev). Many of their works were branded by the central power as “misbegotten,” non-compliant with the dominant narrative. During the WWII years, Tashkent became a significant film hub, in that several important film directors moved from Moscow, Leningrad, and other socialist Republics to the Uzbek capital. Over those years, film production increased in a context of diminished ideological pressure, as many films revolved around historical national themes. In this context, then rehabilitated Nabi Ganiev’s Tohir and Zuhra (Takhir i Zukhra, 1945) is now considered a classic of Uzbek cinema.

A sort of poetic realism runs throughout the sophisticated and cultured film language of Ali Khamrayev, whose works depart from episodes of Soviet history and expose its absurd distortions (Triptych, 1979). The film included in the Festival’s programme, White, White Storks (1966), deals with a still burning topic in the countries of Central Asia as it is connected with women’s self-determination. A close friend of Michelangelo Antonioni and Tonino Guerra, Khamrayev says that his films “have always stood out for human dignity, something for which I often suffered, and still do.”

ALL SCREENINGS ARE FREE